Gadir Gadara

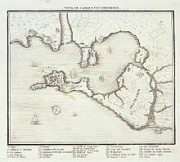

Tartessos (Greek: Ταρτησσός) or Tartessus was a harbor city and surrounding culture on the south coast of the Iberian peninsula (in modern Andalusia, Spain), at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River. It appears in sources from Greece and the Near East starting in the middle of the first millennium BC, for example Herodotus, who describes it as beyond the Pillars of Heracles (Strait of Gibraltar).[1] Roman authors tend to echo the earlier Greek sources, but from around the end of the millennium there are indications that the name Tartessos had fallen out of use, and the city may have been lost to flooding, though several authors attempt to identify it with cities of other names in the area.[2] Archaeological discoveries in the region have built up a picture of a more widespread culture, identified as Tartessian. The Tartessians were rich in metal. In the 4th century BC the historian Ephorus describes "a very prosperous market called Tartessos, with much tin carried by river, as well as gold and copper from Celtic lands".[2] Trade in tin was very lucrative in the Bronze Age, since it is an essential component of true bronze, and comparatively rare. Herodotus refers to a king of Tartessos, Arganthonios, presumably named for his wealth in silver. The people from Tartessos became important trading partners of the Phoenicians, whose presence in Iberia dates from the 8th century BC, and who nearby built a harbor of their own, Gades (present-day Cádiz) The Tartessian script

The Tartessian language is the extinct Paleohispanic language of inscriptions in the Southwestern script found in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula: mainly in the south of Portugal (Algarve and southern Alentejo), but also in Spain (south of Extremadura and western Andalucia). There are 95 of these inscriptions with the longest having 82 readable signs. Around one-third of them have been found in Early Iron Age necropolises or other Iron Age burial sites associated with rich complex burials. It is usual to date them from the 7th century BCE and consider the southwestern script to be the most ancient paleohispanic script with characters most closely resembling specific Phoenician letter forms found in inscriptions dated to c. 825 BC. Meaning of the name Researchers use the term "Tartessian" to refer to the language as attested on the stelae written in the southwestern script (Untermann 1997, Koch 2010, &c.) but some researchers would prefer to reserve the term Tartessian for the language of the core Tartessian zone, attested for these researchers with some graffiti (Correa 2009, p. 277; de Hoz 2007, p.33; 2010, pp. 362-364) like the Huelva graffiti (Untermann 1997, pp.102-103; Mederos and Ruiz 2001) and may be with some stelae (Correa 2009, p. 276): for example Villamanrique de la Condesa (J.52.1). These researchers consider that the language of the inscriptions found outside the core Tartessian zone would be either a different language (Villar 2000, p. 423; Rodríguez Ramos 2009, p.8; de Hoz 2010, p.473) or maybe a Tartessian dialect (Correa 2009, p.278), and so they would prefer to identify the language of the stelae with a different title, namely "southwestern" (Villar 2000; de Hoz 2010) or "south-Lusitanian" (Rodríguez Ramos 2009). There is general agreement that the core area of Tartessos is around Huelva extending to the valley of the Guadalquivir, while the area under Tartessian influence is much wider (Koch 2010 2011 - see maps). Three of the 95 stelae plus some graffiti, belong to the core area: Alcala del Rio (J.53.1), Villamanrique de la Condesa (J.52.1) and Puente Genil (J.51.1). Four have also been found in the Middle Guadiana (in Extremadura) and the rest have been found in the south of Portugal (Algarve and Lower Alentejo) where the Greek and Roman sources locate the Pre-Roman Cempsi and Saefs, Cynetes and the Celtici peoples. History The most confident dating is for the Tartessian inscription (J.57.1) in the necropolis at Medellin, Badajoz, Spain to 650/625 BC. Further confirmatory dates for the Medellin necropolis include painted ceramics of the 7th-6th centuries BC.

In addition a graffito on a Phoenician sherd dated to the early to mid 7th century BC and found at the Phoenician settlement of Doña Blanca near Cadiz has been identified as Tartessian, but is only two signs long. The lecture of the graffito was ]tetu[ or may be ]tute[ and it doesn't show the syllable-vowel redundancy characteristic of the southwestern script (Correa and Zamora 2008).

The script used in the mint of Salacia (Alcácer do Sal, Portugal) from around 200 BCE may be related to the tartessian script, though it has no syllable-vowel redundancy, violations of this are known, but it is not clear if the language of this mint corresponds with the language of the stelae (de Hoz 2010).

The Turdetani of the Roman period are generally considered the heirs of the Tartessian culture. Strabo mentions that "The Turdetanians are ranked as the wisest of the Iberians; and they make use of an alphabet, and possess records of their ancient history, poems, and laws written in verse that are six thousand years old, as they assert." It is not known when Tartessian ceased to be spoken, but Strabo (writing c. 7 BCE) records that "The Turdetanians ... and particularly those that live about the Baetis, have completely changed over to the Roman mode of life, not even remembering their own language any more." Writing

As discussed above, Tartessian inscriptions are in the Southwestern script, also known as the Tartessian or South-lusitanian script. Like all the paleohispanic scripts, with the exception of the Greco-Iberian alphabet, Tartessian uses syllabic glyphs for plosive consonants and alphabetic letters for other consonants. Thus it is a mixture of an alphabet and a syllabary, a system called a semi-syllabary. Some researchers believe these scripts are descended solely from the Phoenician alphabet, others that the Greek alphabet had an influence as well.

The Tartessian script is very similar to the southeastern Iberian script, both in the shapes of the signs and in their values. The main difference is that southeastern Iberian script does not redundantly mark the vocalic values of syllabic characters. This was discovered by Ulrich Schmoll and allows the classification of most of the characters into vowels, consonants and syllabic characters. Unlike the northeastern Iberian script the decipherment of the southeastern Iberian script and specially the southwestern script is not still closed, because there are a significant group of signs without consensus value among the researchers that study this script (Correa 1989, Untermann 1990, Correia 1996, Rodríguez Ramos 2002; de Hoz 2010). Nevertheless, it is commonly accepted that Tartessian did not distinguish between voiced and unvoiced consonants—[t] from [d], [p] from [b], or [k] from [ɡ].

Information also: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tartessos http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cadiz#History http://riversfromeden.wordpress.com/2011/10/27/the-edge-of-the-world-life-in-the-phoenician-colony-of-gadir/ http://meetingpoint.wikispaces.com/Greek+and+Phoenician+Colonizations+in+the+Iberian+Peninsula http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southwest_script http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arganthonios http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bjwDUUAFOxI